BROWN PAPER: Attorney General's Guidance to Government Lawyers - Rule of Unlawful?

Does the Attorney General have the lawful power to issue the guidance he claims will help restore the rule of law?

Introduction

According to the Law Gazette Attorney General, Richard Hermer KC, has announced he will be issuing fresh legal risk guidance for government lawyers.1 This will, according to the article, he claims

seek to raise the standards for calibrating legality’ and empower government lawyers ‘to give their full and frank advice to me and others in government to stand up for the rule of law’

He made the announcement during his delivery of the 2024 Bingham Lecture on the Rule of Law.2 The lecture theme was that the rule of law within the UK, and the UK’s reputation as a rule of law leader on an international stage, are both in need of restoration and renewal. The current government appears, at least according to the AG’s lecture, to have set itself a project of rule of law “restoration and resilience”.

Part of that restoration, it seems, will be to issue new guidance to government lawyers about how they should provide their advice to Ministers. There are, in my view, a number of issues with the content of the current guidance but as the guidance is being revised they are not worth writing a post about. However, a question as to whether or not the guidance is lawful will apply just as much to the new guidance as it does to the current.

The status of Government Lawyers

Lawyers in government are an oddity. You might be forgiven for thinking that government simply employs lawyers in the same was as any civil servant and that’s the end of it. However, it is not as straightforward as that. There are two 19th century Acts we need to look at: the Revenue Solicitors Act 1828 and the Treasury Solicitor Act 1876.3

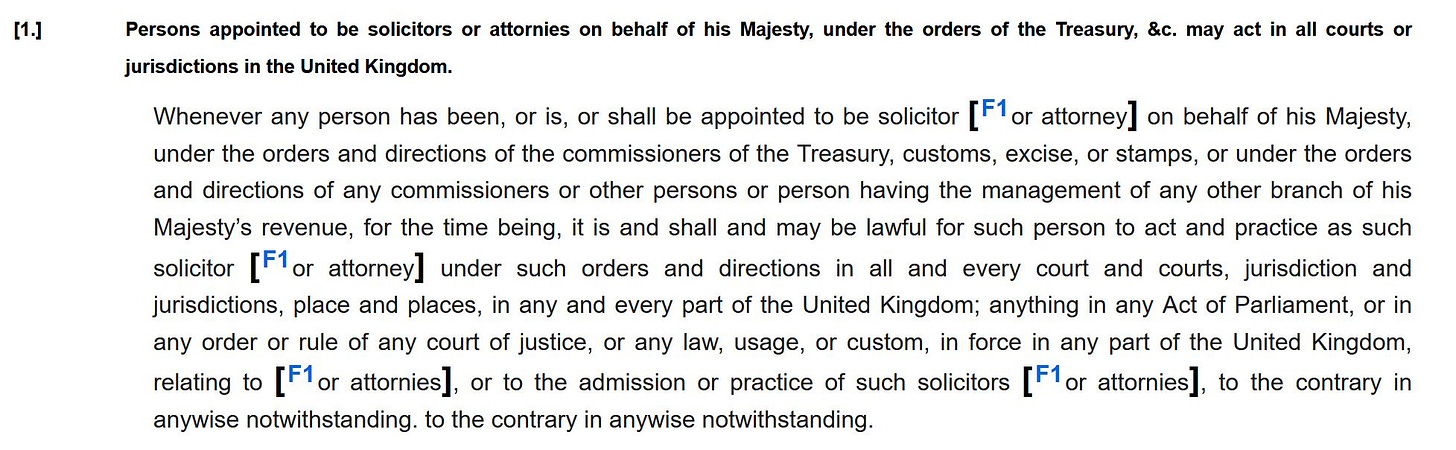

The Revenue Solicitors Act

The Revenue Solicitors Act is the stautory authority by which government lawyers are entitled to practice as solicitors in all parts of the United Kingdom.

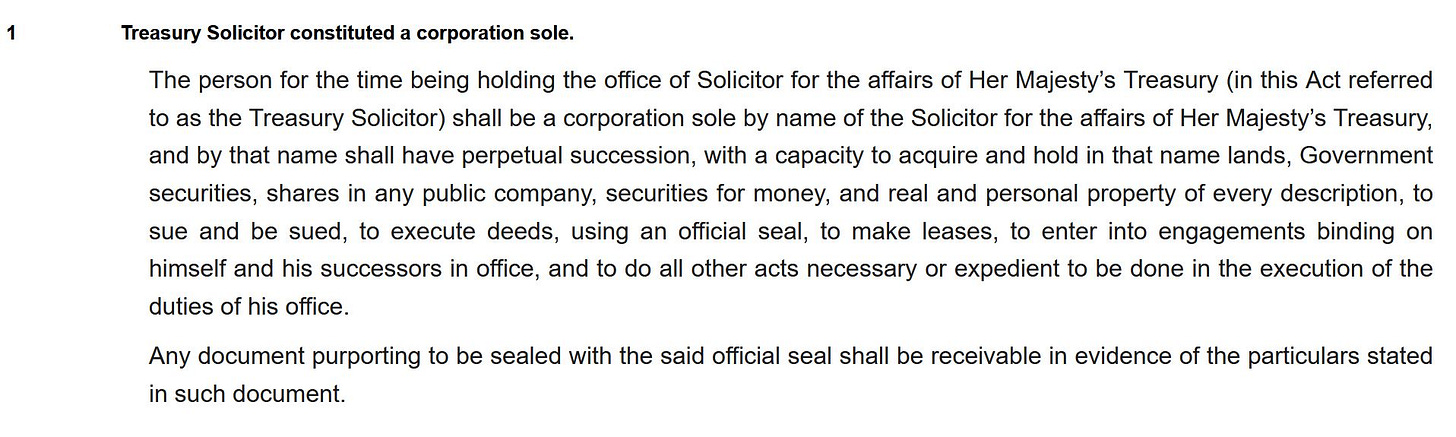

The Treasury Solicitor Act

The Treasury Solicitor Act creates the corporation sole of the Solicitor for the affairs of His Majesty’s Treasury.

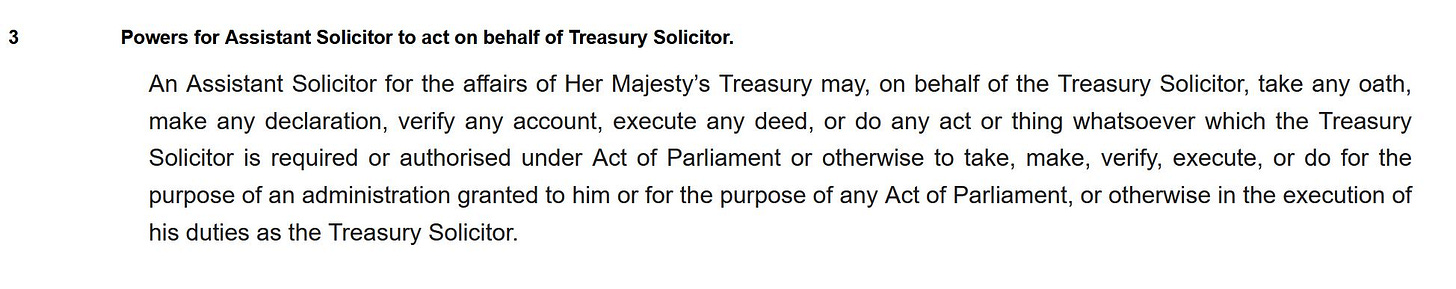

It also empowers Assistant Solicitors for the affairs of His Majesty’s Treasury to act on behalf of the Treasury Solicitor.

Functions of government lawyers

Most lawyers practising in government will be registered, regulated, solicitors and barristers. However, there is no legal requirement for them to be so - the two Acts, taken together, provide a legal basis on which it is lawful to act on behalf of the Crown irrespective of being entitled to practice in the usual manner.

In other words, lawyers practising in government are exercising a stautory function which has been entrusted to them by Parliament. Additionally, the Treasury Solicitor is an office. It is not, therefore, an emanation of the Attorney General. Assistant Solicitors undertake the functions of that office on behalf of the office holder.

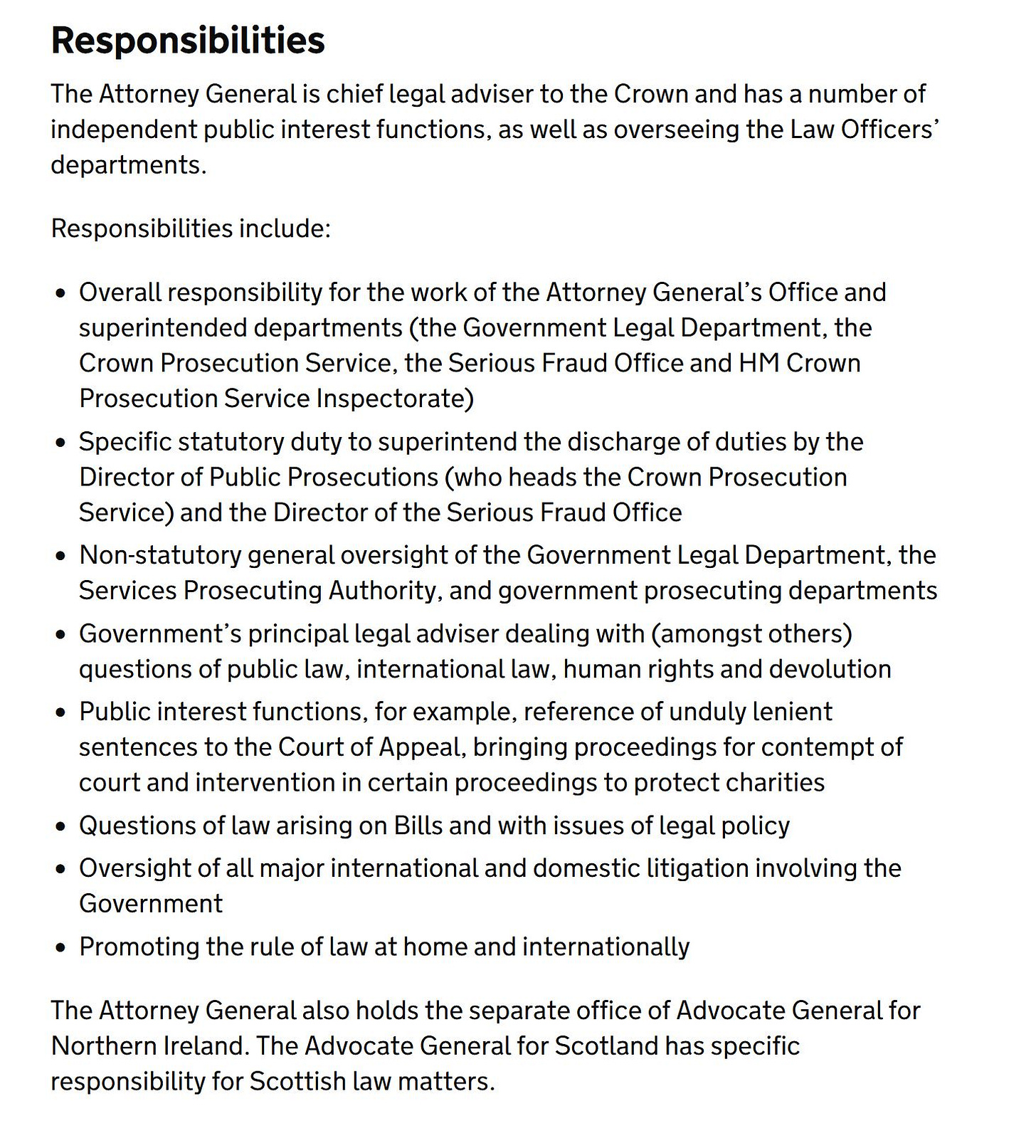

The functions of the Attorney General

The Attorney General is the chief legal advisor to the Crown. The holder has a number of functions, including those which exist in the common law, statutory functions, and “ministerial” type functions within the day to day administration of government.4

Issuing the guidance

As we can see from the above, the Attorney General has been given the responsibility for “work of the superintended departments” and “non-statutory general oversight of the Government Legal Department”. One one view, being asked to take responsibility for the work of the superintended departments should come with the ability to issue guidance about how that work should be undertaken.

However, the work of the “superintended departments”, when it comes to the Government Legal Department and those within it, is arguably entirely derived from a statutory footing. Parliament could have chosen to provide for those functions to be undertaken under the superintendence of the Attorney General, but they did not do so.

In those circumstances it is not immediately obvious from where the Attorney General draws authority to issue guidance on how the statutory functions should be undertaken. One possibility is that it is a residual common law power. If we look back at the wording of the relevant statutes, though, that argument is likely to be unavailable. Both statutes contain within them provisions about issuing “orders” or “rules” and reserve those to people other than the Attorney General. The more likely position is that the field has been occupied by the statutes, and there is no residual common law power.

There does appear to be space for the Attorney General to have “general oversight” of the Government Legal Department in the sense of holding those who run it to account for their running of it. In some ways that does amount to a form of superintendence. There does not, though, appear to be space for him to have responsibility for, superintend, direct, or otherwise give guidance to lawyers employed by the Government Legal Department in the discharge of their functions.

Conclusion

Although there is a basis for the Attorney General to superintend the Government Legal Department, it is far from clear there is a legal basis for him to issue guidance to lawyers exercising their statutory functions on how those functions should be exercised. If guidance is to be issued, it would be more correct for it to be issued by commissioners of the Treasury, who have a power to issue “orders” to revenue solicitors and to make rules about the operation of the Treasury Solicitor Act.

That being said, it is unlikely that a court would intervene and declare the guidance unlawful. The guidance is entirely internally facing; the imposition of the guidance, and the following or otherwise of it, does not impact on the rights of any citizens. It is probable a court would apply similar reasoning to that followed in The Good Law Project, R (On the Application Of) v The Prime Minister & Ors [2022] EWCA Civ 1580.5

However, it does call into question the commitment to the rule of law. Issuing guidance which purports to direct, where there is no power of direction, is in and of itself something which undermines the rule of law. To do so in order to ensure those exercising a statutory function which requires professional independence are fettered in how they exercise that function, doubly undermines the rule of law.

Thank you for reading this brown paper. If you have any comments please

If you’ve found it interesting and would like to see where it leads, or you would like to see how I tackle other topics in future please

You can also let others know about these projects by sharing The Law Drafter

See https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/fresh-legal-risk-guidance-for-government-lawyers/5121199.article for the Law Gazette article.

The text of the AG’s lecture “The Rule of Law in an Age of Populism” can be found here https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/attorney-generals-2024-bingham-lecture-on-the-rule-of-law.

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2022/1580.html. I do not think the case is on all fours, but I do think it would provide a convenient foundation for not intervening in what is, essentially, an internal manual on the provision of advice.