Deproscription of Hamas: A barrister's own goal.

A discussion of the comments made in a clip shared by Times Radio

Introduction

Recently, the currently proscribed terrorist organisation Hamas submitted an application to the Home Secretary to be “deproscribed”. Understandably, as it is a sensitive subject particularly heightened by the events of the last couple of years, this has generated a significant amount of interest on social media.

A lot of that interest was focussed on the lawyers who have assisted Hamas in making the application. Again, this is understandable, and given the previous commentary by some of those lawyers and the swift alteration of the “banner” profile picture of the solicitor’s firm it is difficult to find sympathy with their demands that lawyers should not be associated with the cause of their clients.

I should say, not associating a lawyer with the cause of their clients is, in my view, a fundamental pillar of the rule of law. People, no matter how abhorrent, or no matter how much you disagree with them, need to be able to access assistance and representation to identify, pursue, and defend their legal rights. However, the quid pro quo of that absolutely has to be that lawyers should not do anything which associates themselves with a cause or ideology. Either lawyers are impartial ministers of law and justice, representing without fear or favour to ensure the rights of all are protected, or they are not.

That said, this post is not about the wisdom of not appearing partial if you want to then demand people do not associate you with a cause. Nor will it express a view on the Middle East. It will not express a view on whether or not Hamas should be making the application; as we will see later in the post they have a legal right to do so because Parliament granted them that right.

What I do want to talk about is this clip, posted on Times Radio’s Twitter feed, which shows an extract from an interview with a barrister who was involved in the drafting of the deproscription application and who will, presumably, represent Hamas in any subsequent proceedings.1

In the clip, the barrister indicates a ground of appeal is that the definition of terrorism is “too broad” and

creates an extremely broad discretion […] organisations like the Ukrainian armed forces are clearly caught by the definition. It mostly revolves around things like using violence to achieve a political purpose and, if you just think about that for a moment the armed forces of almost any nation, certainly the Israeli armed forces are caught by that definition

He goes on to say

so one of the arguments we are making is that if you are going to create such a broad discretion, it needs to be subject to legal principles by which it can be challenged.

As we will see later in this post, therein lies the own goal. However, before discussing that, the law.

The Terrorism Act 2000

Terrorism defined

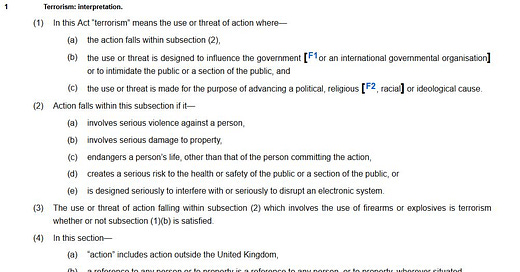

The Act which provides the power to proscribe an organisation is the Terrorism Act 2000. For the purposes of that Act, terrorism is defined as2

I think it is fair to say there is no grounds on which to dispute the barrister’s claim that the definition of terrorism is incredibly broad. Parliament almost certainly intended the definition to be wide-ranging; not least because when faced with the need to deal with serious and/or violent attempts to advance a political, religious, or ideological cause, the last thing anyone really needs is for that need to be held up by years of litigation over whether or not something is terrorism.

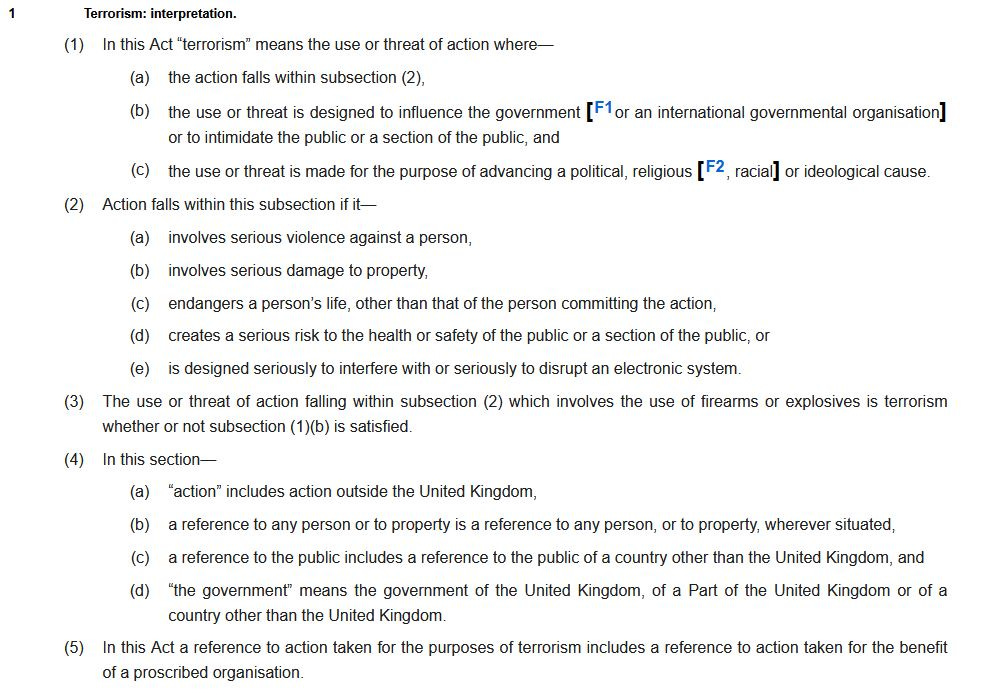

Proscription

The Act contains a list, at schedule 2 to the Act, of organisations which are proscribed organisations.3 There are various offences relating to proscribed organisations (membership, support, uniform), two of which are potentially far-reaching in terms of who may be brought within them.4

Proscription of new organisations is achieved by way of statutory instrument, as is deproscription. The exercise of the statutory instrument power is a discretionary power.

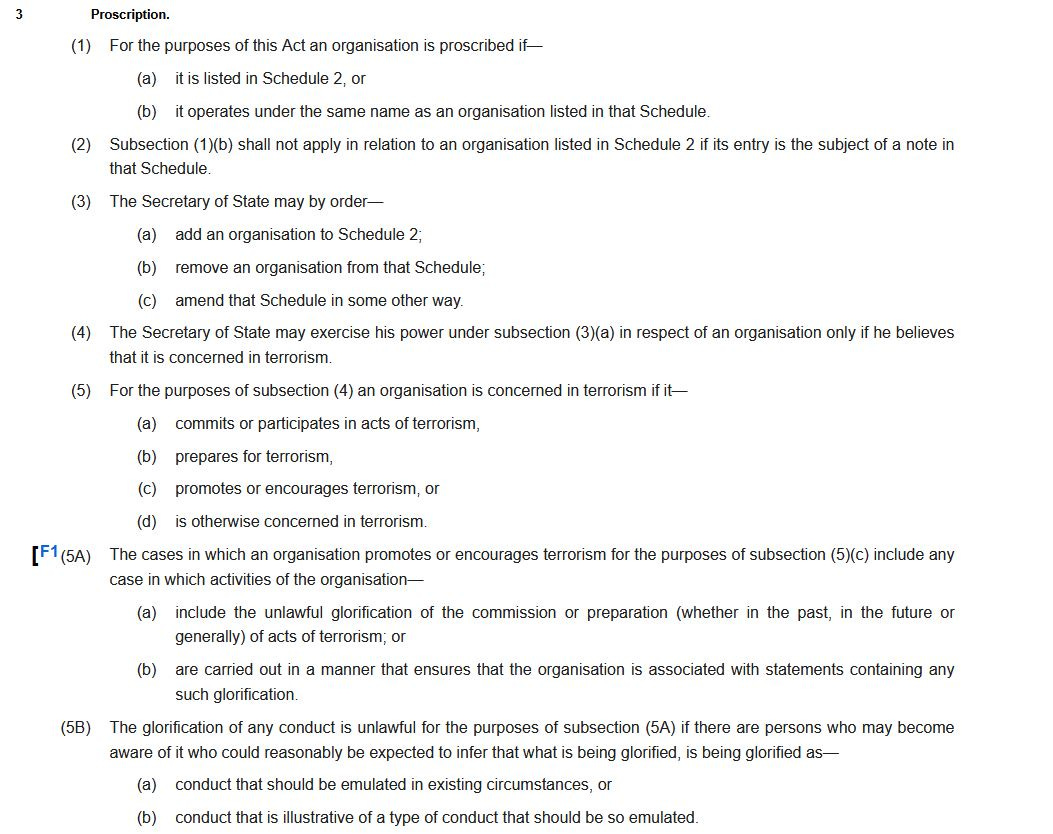

Deproscription

The Act expressly allows for an organisation to apply to the Home Secretary to be removed from the list of proscribed organisations.5 This is, again, a discretionary power

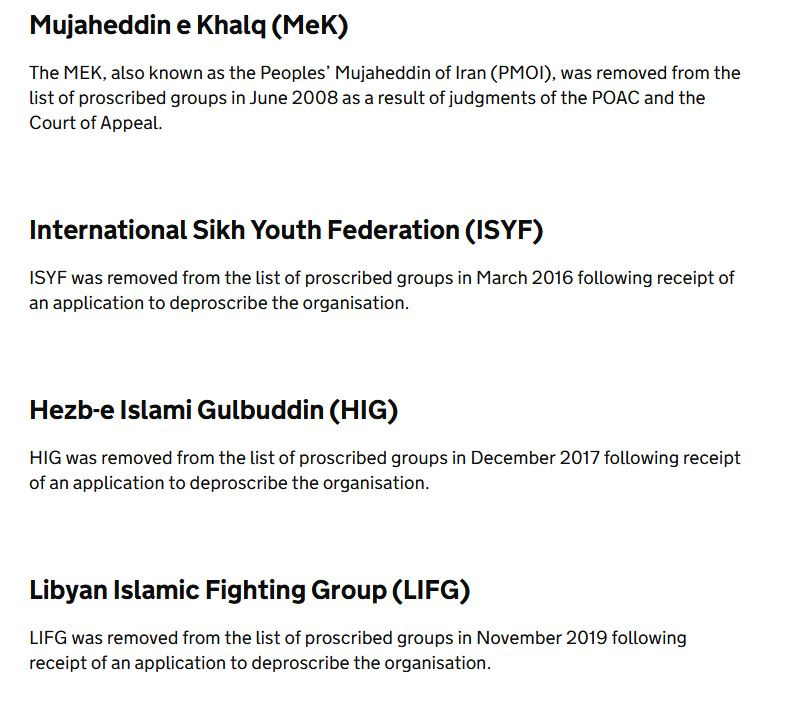

Deproscription is not entirely unheard of, and so it seems fair to say that the discretion has a history of being genuinely exercised. The following organisations have been deproscribed after an application6:

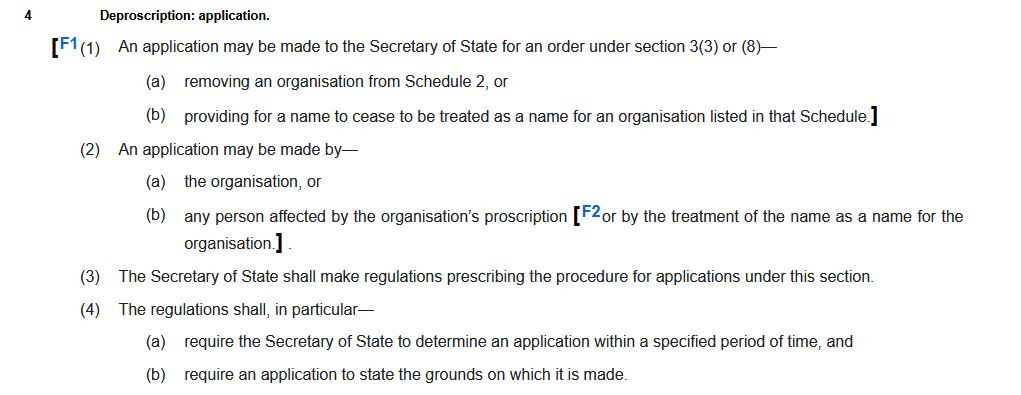

Appeal against decision not to deproscribe

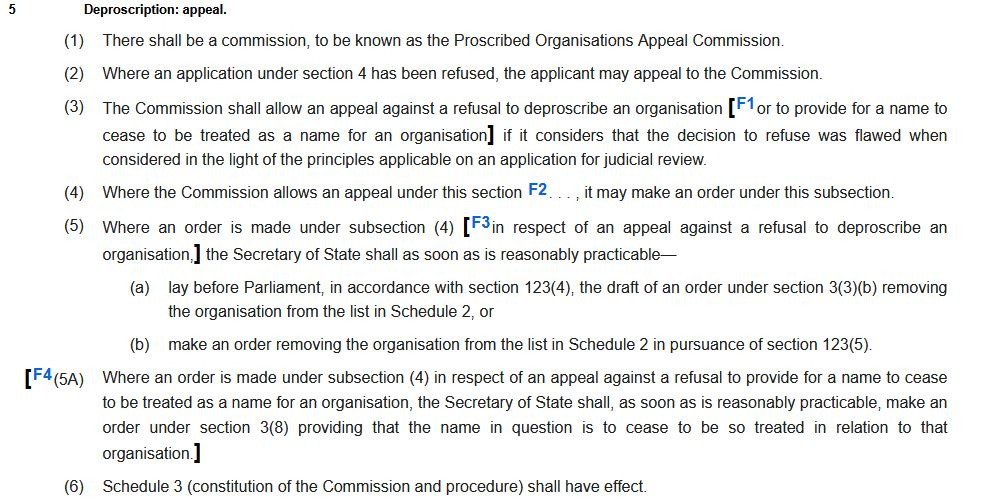

In circumstances where the Home Secretary decides not to deproscribe, the applicant for deproscription has a right of appeal to a little known body known as the Proscribed Organisations Appeal Commission.7 The Commission is, effectively, a specialist tribunal which, when empanelled, consists of one senior judge and two other members.8

The crucial part of section 5, at least for the purposes of this post is subsection (3)

The Commission shall allow an appeal against a refusal to deproscribe an organisation or to provide for a name to cease to be treated as a name for an organisation if it considers the decision to refuse was flawed when considered in light of the principles applicable on an application for judicial review.

In other words, in order to be successful on appeal an applicant needs to show the decision was:

unlawful due to lack of power to take the decision;

irrational;

procedurally improper; or

unfair because the decision maker had given a legitimate expectation they would act in a different way.

The own goal(s)

In the interview, the barrister conceded that Hamas meets the definition of terrorism within the Act. In addition to making the concession, the barrister also hinted at two grounds which are being advanced in the application for deproscription. The first seems to be that the definition of terrorism is simply too broad. The second seems to be that other groups which meet the definition (including, apparently, the Ukrainian army) have not been and so it is unfair to proscribe Hamas.

Conclusion

Own goal 1: conceding Hamas are terrorists.

That Hamas meets the definition of terrorism and is liable to proscription is, on even the very highest case the applicants could put, inescapable and so, therefore, is the concession. However, in making that concession it is difficult to see how the applicants are going to show the (inevitable) refusal to deproscribe was flawed.

The Home Secretary clearly has the power to make the decision, so the first ground of appeal is not in play. I strongly suspect there has not been any legitimate expectations given, so the final ground of appeal is not in play. That leaves procedural impropriety and irrationality.

Procedural impropriety should be relatively easy for the Home Secretary to guard against - if they ensure the application for deproscription is dealt with in accordance with any relevant guidance, the applicant is given a fair hearing and the ability to make representations, and any reasons for the decision are adequately explained, then the ground of appeal is unlikely to be made out.

Decisions on proscription and deproscription need to be made on the available facts, evidence, and intelligence pertaining to the organisation in question. The proscription or otherwise of other organisations is unlikely to be a relevant consideration. The applicant will, on appeal against the (inevitable) decision to refuse the application to deproscribe be in some difficulty making a compelling argument why the status of other organisations is relevant to a decision on Hamas.

Any argument that the definition of terrorism within the Act is too broad is one which needs to be made by politicians in Parliament. The Home Secretary does not have the power to deproscribe an organisation on the basis the definition is too broad; to do so would be to take into account an irrelevant consideration and would be irrational. It is difficult to see the Commission entertaining the argument the definition is too broad.

Own goal 2: abuse of process

Leaving aside the difficulties in making the arguments, the comments in the interview risk giving the impression that the application, and the appeal which will follow, are an abuse of process. If the real issue complained of is that the definition within the Act is too broad then the Commission is not the place to bring that complaint.

If the issue complained of is that Hamas is proscribed, despite the admission it is a terrorist organisation, but others are not then, again, the Commission is not the place to bring that complaint.

“Subject to legal principles by which it can be challenged”

This is, perhaps, the oddest part of the interview clip. The decisions about proscription are, clearly, subject to legal principles by which they can be challenged. It says so in the Act. They also require Parliamentary approval of the legislation which gives effect to the decision.

If an organisation is proscribed it can ask to be deproscribed. A refusal to deproscribe can be appealed to an independent, specialist, tribunal which is able to determine if the Home Secretary’s decision was flawed “when considered in light of the principles applicable on an application for judicial review”.

There could not be a clearer indication that the decision is subject to legal principles by which it can be challenged.

A pyrrhic victory

Even if an appeal to the Commission is successful, it might not lead to deproscription. The Commission has the power to order the Home Secretary to lay an order before Parliament who may simply refuse to approve it.

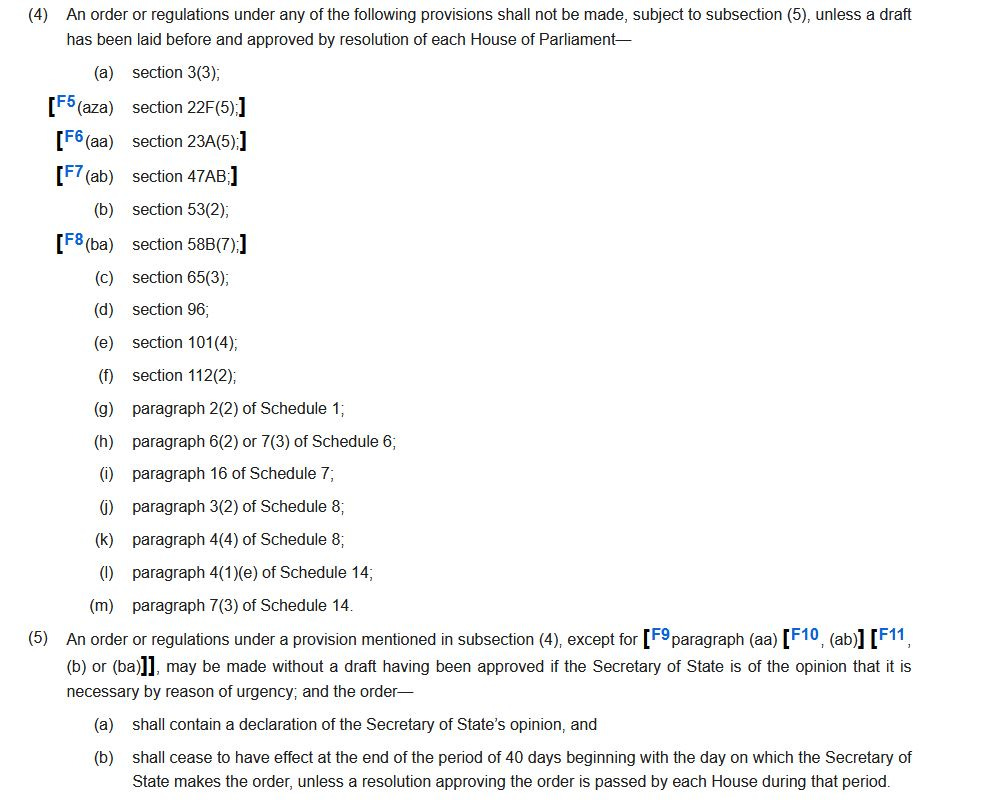

The order to deproscribe is made under section 3(3) of the Act. Section 123 of the Act sets out the Parliamentary controls on that order.9 Either the order must be laid in draft and approved by both houses or, if it is made as a matter of urgency, continued in effect by resolution of both houses.

Given the concession that Hamas is a terrorist organisation, it seems unlikely Parliament would allow its deproscription.

Thank you for reading this post. If you have any comments please

If you’ve found it interesting and would like to see where it leads, or you would like to see how I tackle other topics in future please

You can also let others know about these projects by sharing The Law Drafter

The clip can be found here https://x.com/TimesRadio/status/1910660040089813247.

The definition of terrorism can be found at section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2000.

An organisation is proscribed by combination of section 3(1) of, and schedule 2 to, the Terrorism Act 2000.

These are set out in sections 11 to 13 of the Terrorism Act 2000. The reason I say they are “potentially far-reaching in terms of who may be brought within them” is that, for example, the uniform offence is complete where a “reasonable suspicion that the person is a member or supporter of a terrorist organisation" is aroused; it is, therefore, possible to commit terrorism offences without actually supporting a terrorist organisation. Such is the reach of those offences, that immunity is expressly provided for the purposes of applications for deproscription and appeals relating to that process.

A proscribed organisation, or anyone affected by proscription, may apply pursuant to section 4 of the Terrorism Act 2000 to the Home Secretary asking them to make a statutory instrument removing the organisation from schedule 2 to the Act.

The right to appeal against a decision of the Home Secretary not to deproscribe can be found in section 5 of the Terrorism Act 2000.

For a little more information, see https://www.gov.uk/guidance/appeal-against-a-ban-on-your-organisation.

Very interesting, thank you.

I think there are a couple of words missing from this sentence:

The Commission has the power to order the Home Secretary to lay an order before Parliament may simply refuse to approve it.